4 Surveying Current Digital Self-Control Tools’ Effectiveness and Challenges

4.1 Introduction

As outlined in Chapter 2, existing studies developing and/or evaluating interventions for digital self-control have begun to build an understanding of how design patterns ranging from visualisations of time spent (Whittaker et al. 2016) to goal-setting with social support (Ko et al. 2015) may support self-regulation of digital device use. However, we are in the early days of collecting evidence on the potential effectiveness across the design space of such patterns, the contexts in which they are useful, and the extent to which their effectiveness depends on individual differences (J. Kim, Jung, et al. 2019; G. Mark, Czerwinski, and Iqbal 2018).

While controlled studies are appropriate and feasible for evaluating and comparing a small number of interventions, they are difficult to scale for broadly assessing a large number of design patterns and implementations. A complementary approach, which can help scope the range of design patterns and implementations to explore in controlled studies, is to investigate the landscape of digital self-control tools (DSCTs) on app and web stores (Lyngs et al. 2019; Roffarello and De Russis 2019a; van Velthoven, Powell, and Powell 2018). Here, widely available tools potentially represent hundreds of thousands of natural ‘micro-experiments’ (Daskalova 2018; J. Lee et al. 2017) in which individuals self-experiment with apps that represent not only one or more design patterns, but particular designs for implementing those patterns. One indicator of the outcome of such micro-experiments is store ratings, user numbers, and reviews, which may provide information about user needs, contexts of use, and the relative utility of design patterns and implementations.

Other domains of research have benefitted from this approach, e.g., mental health (Bakker et al. 2016; Huguet et al. 2016; Lui, Marcus, and Barry 2017; Sucala et al. 2017) where thematic analysis of public reviews has been used to explore factors important for optimising user experience and support engagement in apps for cognitive behavioural therapy (Stawarz et al. 2018). However, few studies on digital self-control have taken this route: excluding the present thesis work, three studies have described and/or categorised functionality in samples of digital self-control tools available online (Biskjaer, Dalsgaard, and Halskov 2016; Roffarello and De Russis 2019a; van Velthoven, Powell, and Powell 2018): van Velthoven, Powell, and Powell (2018) presented aims and features in 21 tools identified via the software recommendation platform alternativeto.net; Biskjaer, Dalsgaard, and Halskov (2016) presented a taxonomy of functionality based on 10 tools from Google Play, Chrome Web, and Apple App stores and online tech magazines; and Roffarello and De Russis (2019a) presented a taxonomy of functionality based on 42 mobile apps from the Google Play store. Only one study has analysed user reviews: Roffarello and De Russis (2019a), who conducted thematic analysis of 1,128 reviews from the 42 mobile apps they identified.

None of these studies incorporated store metrics of popularity, such as number of users, into their analyses. In research on digital tools for cognitive behavioural therapy, however, such information has fruitfully been used to investigate, e.g., whether store popularity correlates with presence of evidence-based features (Kertz et al. 2017). Similarly, combining functionality in digital self-control tools with metrics such as user numbers and average ratings could provide basic evidence allowing us to investigate whether feature types and combinations predict store popularity.

Moreover, thematic analysis of user reviews may yield different insights depending on how reviews are sampled across tools with different functionality, and depending on the specific strategy for analysing them (N. Chen et al. 2014; Virginia Braun et al. 2018). The existing study of user reviews did not include information about how the reviews analysed were distributed across apps with different functionality (Roffarello and De Russis 2019a), and so conducting additional thematic analyses with transparent sampling of reviews would be helpful.

In the present chapter, we therefore extend Chapter 3’s functionality analysis by using additional information from the publicly-available app and web store listings as a resource representing user self-experimentation with these tools. Specifically, we conduct a combined analysis of tool functionality, user numbers, average ratings, and the content of reviews for 334 DSCTs drawn from the work presented in Chapter 3.

In doing so, this chapter makes three research contributions:

- An analysis of how design features and feature combinations are associated with popularity metrics (user numbers and average ratings), providing a reference point for relative popularity of design patterns and implementations

- A thematic analysis of 961 user reviews sampled across tools with different types of functionality, drawing out contexts of use and key design challenges from the review content

- A set of research materials comprising scrapers, analysis scripts, and data, including ~55,000 anonymised reviews, made available via the Open Science Framework on osf.io/t8y5h/

Our analysis of user numbers and ratings finds that DSCTs which combine two or more types of design patterns in their functionality receive higher ratings than tools implementing only one. Moreover, DSCTs that include goal advancement features rank higher on average ratings than on user numbers, suggesting that they might be effective but less likely to ‘go viral.’ Our thematic analysis of reviews finds that DSCTs are used in contexts where people focus on tasks that are important, but not immediately gratifying. Moreover, users search for tools which provide a level of friction or reward that is ‘just right’ for encouraging intended behaviour without being overly restrictive or annoying (with the ‘just right’ level differing between people), and which can capture their personal definition of ‘distraction.’

This chapter’s dataset may be used in future work as reference for ‘better’ or ‘worse’ implementations of specific strategies as judged by users on app and browser extension stores. In addition, reviews may be sampled from the full dataset in numerous ways for thematic analysis in relation to specific research questions, and therefore provide potential value for other researchers investigating, e.g.‚ how best to implement specific design patterns such as lockout mechanisms (J. Kim, Jung, et al. 2019).

4.2 Methods

Materials and data for the paper on which the present chapter is based are available on osf.io/t8y5h/.

We investigated the same 367 digital self-control tools reviewed in Chapter 3, as this represented the largest review to date, and used Chapter 3’s classification of four main types of design patterns expressed by the features of these tools:

- block/removal (features for blocking distractions, such as temporarily locking the user out of specific apps, or for removing them in the first place, such as hiding the newsfeed on Facebook)

- self-tracking (features for tracking and/or visualising device use)

- goal-advancement (features for reminding the user of their usage goals)

- reward/punishment (features that provide rewards or punishments for the way in which devices are used)

4.2.1 Collecting tool information and user reviews

In March 2019, we collected additional information about these tools (including number of users, average ratings, and their latest store descriptions), as well as user reviews publicly available on their store pages.

For apps on the Google Play store, we used a pre-existing script (Olano 2018b) to download tool information and reviews.

For apps on the Apple App store, we used a pre-existing script (Olano 2018a) to download reviews, and wrote our own script (using R packages rvest and RSelenium) to collect tool information.

As the script for obtaining reviews from the Apple App store sometimes failed to retrieve all reviews visible on tools’ store page, we wrote an additional R script for collecting reviews when manual inspection found some to be missing.

For extensions on the Chrome Web store, we wrote an R script to download tool information and reviews.

4.2.2 Analysing user numbers and ratings

All stores displayed average ratings as well as number of ratings. However, the stores provided different types of information in relation to user numbers: The Chrome Web store provided an exact number of users for an extension, and the Google Play store provided a ‘minimum number of installs’ (e.g. ‘100,000+’). The Apple App store provided no direct information about user numbers. For tools on the Apple App store we therefore used number of ratings as a proxy for relative number of users in analyses where tools were ranked by number of users.

4.2.3 Thematic analysis

To cover the design space, we first sampled up to 20 reviews from each of the 5 tools with the highest number of users, from each store6, from each main functionality type that were assigned to tools as their first category. As functionality types were not evenly distributed across stores (for example, blocking tools are rare on the Apple App store), we subsequently randomly sampled additional reviews, from tools targeting each type of functionality, for a total of 961 reviews (cf. Roffarello and De Russis 2019a).

Next, we conducted an inductive thematic analysis, following the ‘reflexive’ approach described in V. Braun and Clarke (2006) and Virginia Braun et al. (2018). First, we read through all the reviews and conducted an initial coding of recurrent patterns in the data relevant to our research aims. Subsequently, we read through all extracts associated with each code, recoded instances, and iteratively sorted codes into potential themes, and discussed emerging themes.

We used the Dedoose software for thematic analysis, and R for all quantitative analyses.

4.3 Results

33 tools had become unavailable since we conducted the review presented in Chapter 3. Hence, we were able to collect additional information for 334 tools: 212 extensions from Chrome Web, 71 apps from Google Play, and 51 apps from the Apple App store.

260 of these tools had received user reviews (160 from Chrome Web, 77 from Google Play, and 23 from the Apple App store). From these, we collected a total of 54,320 reviews (9,071 from Chrome Web, 44,701 from Google Play, and 548 from the Apple App store).

The dataset on the Open Science Framework includes user numbers, ratings, and functionality for all tools — including Chater 3‘s granular feature analysis which, e.g., breaks down ’block/removal’ into specific features such as time limits, launch limits, and friction for overriding blocking — as well as all collected reviews.

4.3.1 User numbers and ratings

For DSCTs from the Google Play store, the median ‘minimum number of installs’ was 10,000 (min = 5, max = 5,000,000), from the Chrome Web store, the median number of users was 194.5 (min = 1, max = 1,736,018)), and from the Apple App store, the median number of ratings was 0 (min = 0, max = 14,900). The median average rating given to tools (for tools with more than 30 ratings) was 4.3 (individual ratings range from 1 to 5 stars on all three stores; 5 is best).

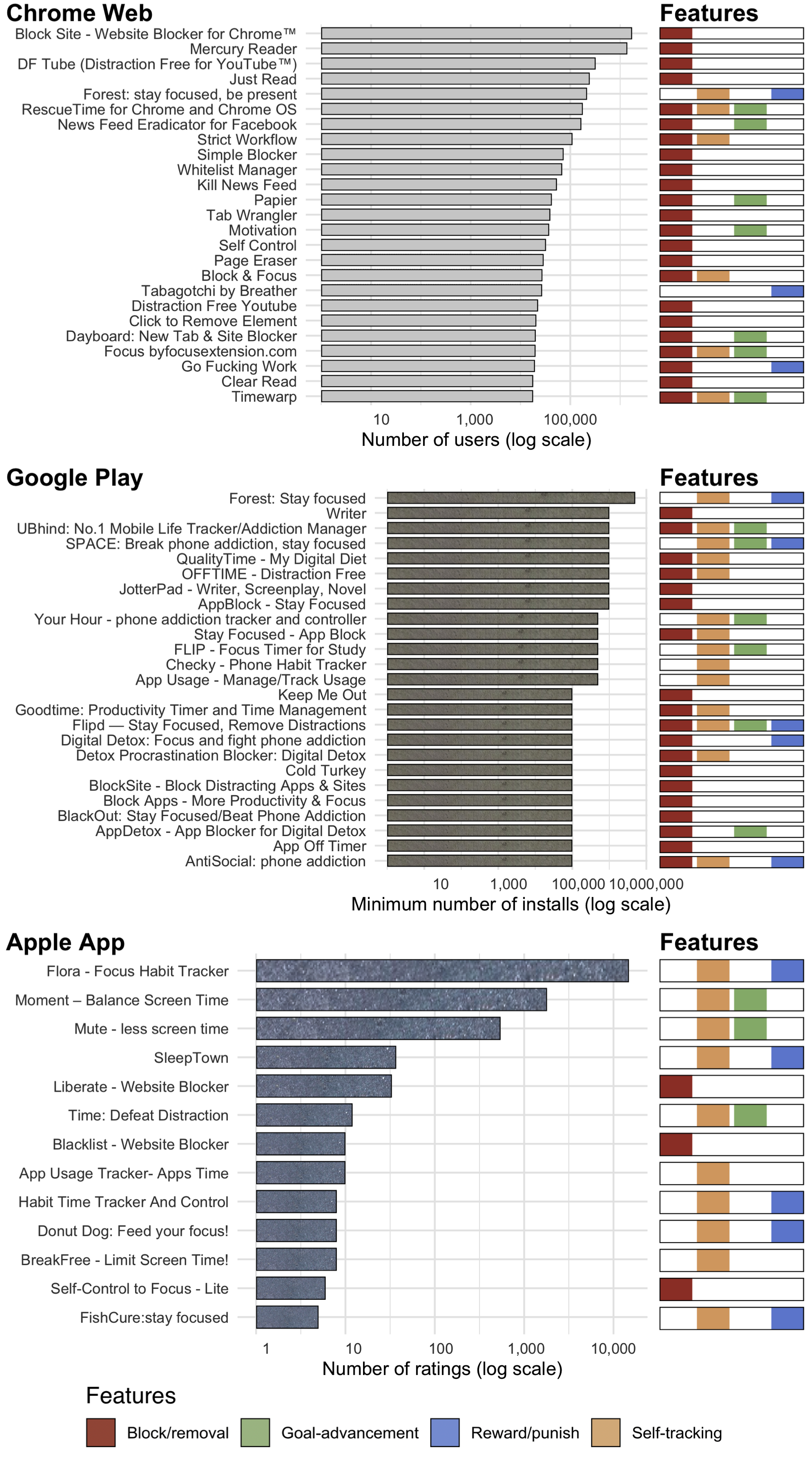

Figure 4.1: Top tools in terms of number of users (on Apple App store, ranked by number of ratings as this store provides no direct information about user numbers). Reward/punishment is the least common type of design feature among top tools, but two tools including such functionality (Forest and Flora, which gamify self-control by growing virtual trees) have the highest user numbers on Google Play and Apple App, and rank in top 5 on the Chrome Web store. Block/removal features are very common on Google Play and Chrome Web, but rare on the Apple App store.

Figure 4.1 shows top tools in terms of number of users and their types of features (on the Apple App store, ranked by number of ratings; only 13 tools from this store had received any ratings). The distributions of feature types in top tools differed by store, mirroring differences between stores overall (cf. Chapter 3) — for example, block/removal functionality is rare on the Apple App store compared to the Google Play and Chrome Web store.

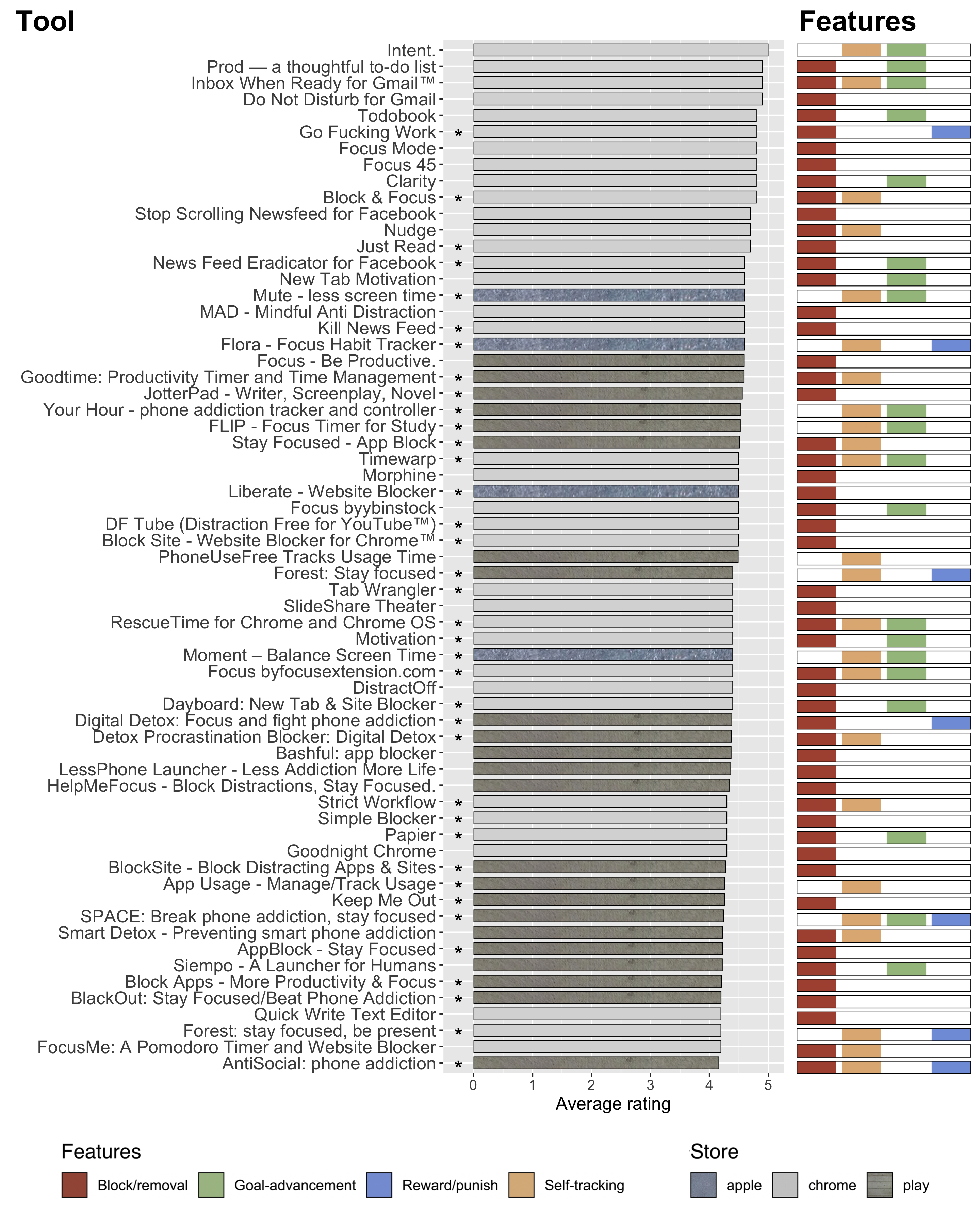

Figure 4.2: Top tools ranked by average rating (for tools with more than 30 ratings). Tools marked with an asterisk also appear on the plots of top tools ranked by user numbers (Figure 4.1). Tools that include goal advancement features are more common among top tools in terms of average ratings than they are in terms of user numbers.

Figure 4.2 displays top tools in terms of average rating (to obtain a representative sample underlying the average, this figure includes only tools with more than 30 ratings; only 5 tools from the Apple App store had received more than 30 ratings). 59% (37 out of 63) of tools shown in Figure 4.2 also appear in Figure 4.1, suggesting that tools with higher user numbers have a large overlap with tools with higher ratings.

Reward/punishment features were the least common in top tools, but some tools implementing such features ranked highly: Forest and Flora, which both gamify self-control by growing virtual trees or plants, topped the number of users on the Google Play and Apple App stores, and Forest was in the top 5 on the Chrome Web store.

Goal advancement features were more common among top tools ranked by average rating (32%, 20/63) than by number of users (25%, 16/63), and than the overall prevalence of this feature type (22% of tools, 75/334).

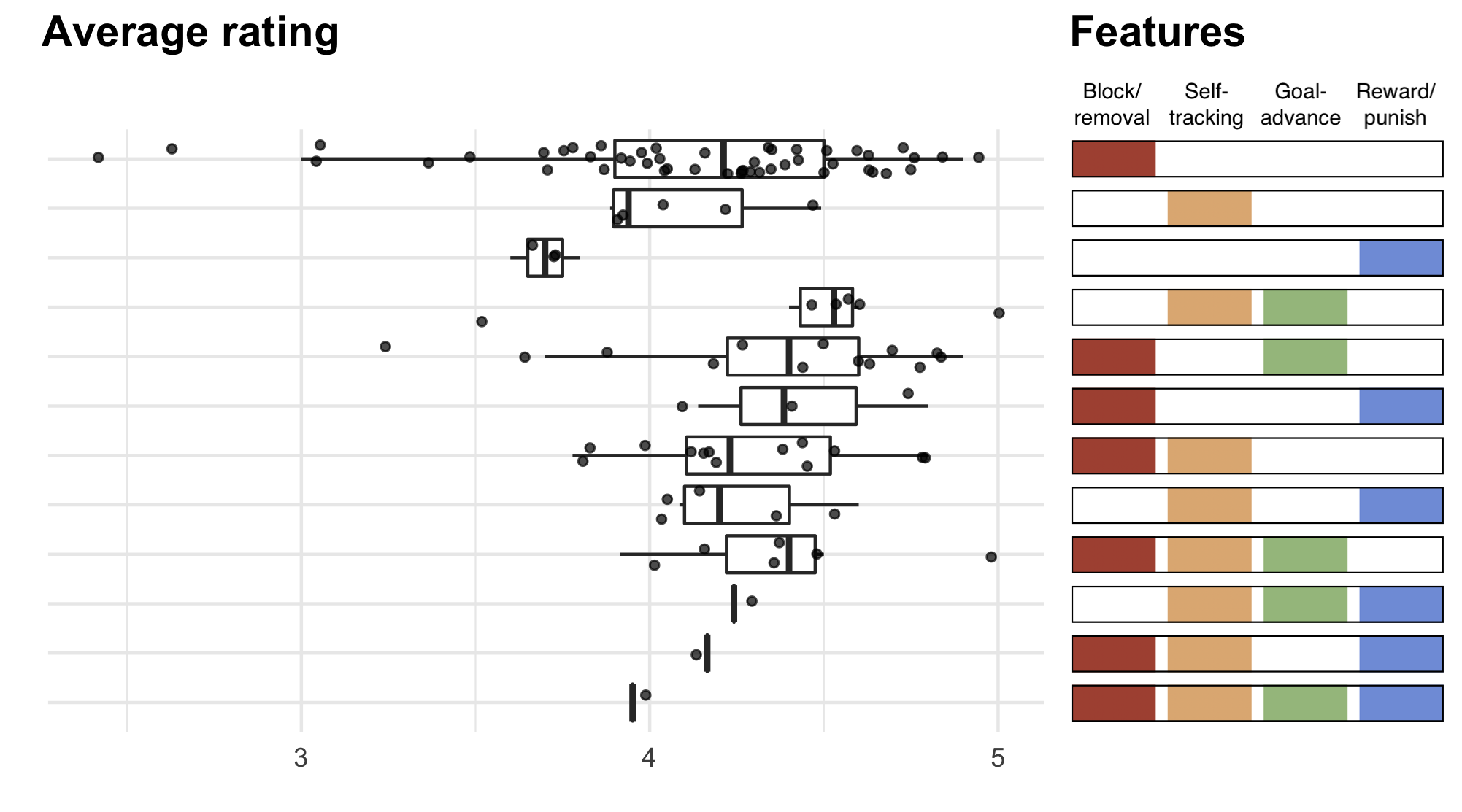

Figure 4.3: Average ratings by feature combination (for tools with more than 30 ratings). Tools combining more than one type of features have higher average ratings (median = 4.39) than do tools implementing a single type (median = 4.2, p = 0.008, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test).

Across all tools, 64% implemented a single type of design pattern, whereas 32% combined two — very few combined three (3%) or all four (1%, cf. section 3.3.2.2). Tools whose features combined two or more types of design patterns had significantly higher average ratings than tools which implemented a single type (comparing tools with more than 30 ratings; median average rating with a single type = 4.2, median for tools combining two or more = 4.39, p = 0.008 in Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test, cf. Figure 4.3).

4.3.2 User reviews

Figure 4.4: Word cloud depicting frequencies of terms across all collected reviews (excluding the terms ‘app/s,’ ‘phone,’ and ‘extension’). Font size indicate relative frequency. Colouring is aesthetic and does not map to any characteristics of the data.

| Number of occurrences | Phrase |

|---|---|

| 257 | time limit/s |

| 226 | usage time |

| 175 | screen time |

| 172 | time spent |

| 137 | waste/wasting time |

| 103 | time management |

| 103 | set time |

| 72 | break time |

| 69 | quality time |

| 66 | phone time |

| 62 | time wasting |

| 58 | time period |

| 53 | study time |

| 51 | specific time |

| 44 | focus time |

The median number of reviews for a tool was 6 (min = 1, max = 4600), and the median number of words in a review was 14 (min = 1, max = 640). Figure 4.4 shows the overall frequency of terms used in reviews, excluding the terms ‘app/s,’ ‘phone’ and ‘extension.’ Apart from ‘app’ (46% of reviews), the most frequent term was ‘time,’ which was included in 17.5% of all reviews. The terms most commonly following or preceding ‘time’ included ‘usage,’ ‘limit,’ ‘screen,’ ‘spent,’ ‘set,’ ‘management,’ and ‘wasting’ (see Table 4.1), suggesting that managing time spent on digital devices was one of the most central topics.

Thematic analysis

| Design pattern combination | Number of tools | Number of reviews |

|---|---|---|

| Block/removal | 19 | 152 |

| Reward/punish | 6 | 146 |

| Self-tracking | 9 | 147 |

| Goal-advancement | 10 | 27 |

| Block/removal + Reward/punish | 1 | 20 |

| Block/removal + Self-tracking | 5 | 99 |

| Reward/punish + Self-tracking | 12 | 104 |

| Block/removal + Goal-advancement | 4 | 76 |

| Goal-advancement + Self-tracking | 6 | 75 |

| Block/removal + Reward/punish + Self-tracking | 1 | 21 |

| Block/removal + Goal-advancement + Self-tracking | 3 | 60 |

| Goal-advancement + Reward/punish + Self-tracking | 2 | 27 |

| Block/removal + Goal-advancement + Reward/punish + Self-tracking | 1 | 7 |

We conducted thematic analysis of 961 reviews from a total of 79 different apps (cf. Table 4.2). Our early codes resembled those reported by Roffarello and De Russis (2019a). Thus, our initial codes were grouped into ‘positive,’ ‘neutral’ and ‘negative,’ with frequently occurring codes including: generic praise or critique; bug complaints; feature suggestions; contexts of use; benefits of use; feedback on UI and performance; descriptions of functionality; comparisons to other tools; and privacy concerns.

An early observation, as we explored reported benefits of use, was that a substantial proportion of reviews expressed highly positive and important impact of use (n = 214, 22% of reviews). The review content commonly suggested that users felt a lack of control over ordinary digital device use, which resulted in using them in unintended ways, or in using them so much that it interfered with other goals. However, DSCTs were seen as effectively helping users take back control (“Helped me regain my time and attention on the web.” R328, Intent, “This app saved my life. It made me realise just how bad my addiction to my tablet was and motivated me to reduce my time on it and to spend more time doing other things, like reading.” R647, Moment), and many thanked developers for this (“Thank you again you saved my sanity,” R768, App Usage). Some reviews expressed surprise or even embarrassment that particular tools had been useful to them (“A little embarrassed it works for me but hey I am more focused and thats all that matter,” R614, Tabagotchi).

As we iteratively worked further with the codes and excerpts, in keeping with a reflexive approach to thematic analysis (Virginia Braun et al. 2018), our analysis revealed four key themes capturing more actionable insights in relation to DSCTs’ use contexts and design challenges: (i) DSCTs help people prioritise important but effortful tasks over guilty pleasures, (ii) DSCTs are useful because many default designs overload users with information or tempting options, which leads to self-regulatory failure, (iii) DSCTs should provide a level of friction or reward that is ‘just right’ for encouraging behaviour change, (iv) DSCTs should adapt to personal definitions of ‘distraction.’

Theme 1: DSCTs help people prioritise important but effortful tasks over guilty pleasures

The contexts in which tools were used suggested that they are particularly helpful when people try to focus on tasks that are important, but not immediately gratifying, and are tempted to engage in alternative ‘guilty pleasures’ easily accessible on their devices (n = 84, 9% of reviews).

Some reviews expressed this as DSCTs helping overcome ‘procrastination’ (“This extension saved me from the procrastination monster,” R816, Block Site - Website Blocker for Chrome). Others explicitly said the tools helped them resolve internal conflict between different urges and emotional states in line with their longer-term goals (“helps me untangle my internal conflicts around my internet usage,” R405, Intent; “helps control the impulse to constantly and unnecessarily control my mailbox,” R545, Inbox When Ready for Gmail; “If you unconsciously glide from necessary info surfing to unnecessary stuff OR If you unconsciously open browser because you are getting bored,” R724, Guilt).

In terms of more specific contexts, many reviews contributing to this theme (54%) said DSCTs helped them in productivity or work contexts (“I don’t wish to waste my time on social media but somehow I skip the track of time and so many work gets pending,” R463, HelpMeFocus; “Only installed it a couple hours ago, and I already completed 7 to do items that I had be putting off for week,” R664, PAVLOK Productivity). Other contexts commonly mentioned included studying (24%), writing (11%) and going to sleep (10%). In terms of studying, reviews said tools were used by students to focus on schoolwork, and by teachers to make students more focused in class. In terms of writing, reviews expressed that a distraction-free digital environment helped writers complete their tasks (“I recommend this for writers everywhere who just want an elegant and interruption-free tool to get their stuff done,” R700, Just Write). In terms of sleep, reviews expressed that device use often interfered with going to bed at the intended time (“I always used to stay up really late on my phone until I got this app,” R163, SleepTown), but that digital self-control tools helped users adjust their habits in favour of the sleep patterns they wanted (“I use it to stop myself from using my phone at least 30 minutes before bed,” R804, AppBlock; “I love that this app has helped me curb my late-night phone habits,” R386, Off the Grid; “This has genuinely helped get into a better sleeping habit for me!” R819, SleepTown).

Sub-theme: DSCTs are particularly useful for people for whom self-control struggles are more acute

A sub theme implied by some reviews was that digital self-control tools are particularly useful for people for whom self-control struggles over digital device use are more acute (n = 26, 2.6%).

Most often (81% of reviews contributing to this subtheme), this was expressed in the form of people labelling themselves ‘addicts’ to digital technology, as easily addicted in general (“I’m a kid and I can get addicted to things really quick and this has helped me a lot,” R817, SPACE), or as general ‘procrastinators’ (“I am a horrible procrastinator and I will distract myself with anything,” R298, Flora). At a more clinical end of the spectrum, a reviewer who found the app Flora helped them focus on schoolwork also said they were “recently diagnosed with severe ADHD” (R303).

Theme 2: DSCTs are useful because many default designs overload users with information or tempting options, which leads to self-regulatory failure

DSCTs sometimes received positive reviews because they were seen as directly countering information overload in default designs, or outright ‘dark design patterns,’ that caused self-control problems (n = 46, 5% of reviews).

For example, some users felt default interfaces for email inboxes caused them trouble, which they could correct with the right DSCT (“Can’t tell you how many times I just wanted to do one thing in my email and got lost in my inbox. Wish I had this years ago.” R190, Inbox When Ready for Gmail). Other reviews expressed that DSCTs helped them counteract tech companies’ malevolent ‘attention hacking’ (“Mark Zuckerberg’s evil masterminds only want to maximize the time you stay on Facebook by making you keeping scrolling, watching stupid videos and worthless news. Now there’s nothing to scroll :),” R708, News Feed Eradicator for Facebook).

Many reviews contributing to this theme (80%) mentioned that a tool provided a piece of functionality or design tweak that users needed or had deliberately searched for (“Just What I Need… Now I can use Facebook for what it’s useful for,” R541, Clar, “This is exactly what I was looking for!” R830, FocusMe, “I googled ‘chrome extension are you sure’ hoping that someone had thought of this plugin. Sure enough, here it is,” R358, Are you sure?, a Chrome extension that pops up a simple dialog box asking “Are you sure?” when the user navigates to a distracting website).

Theme 3: DSCTs should provide a level of friction or reward that is ‘just right’ for encouraging behaviour change

Users searched for tools that provided a level of friction or reward which brought about their intended change in behaviour without being overly restrictive or annoying (n = 85, 9% of reviews). Reviews implied a spectrum of individual differences in where this ‘Goldilocks level’ was, with some reviews stating that simply tracking and visualising past behaviour was sufficient to change behaviour (“The visualization showing how many times I open my Twitter app has helped me change my habits on its own,” R794, Intent), whereas others needed heavy-handed support and, e.g., wanted to make it impossible for themselves to override blocking of distractions (“Easy to bypass I’ve searched through the settings and there is no ‘no manual exit’ option,” R960, OFFTIME).

Thus, for blocking tools, users sometimes complained that they were ‘too strict,’ and made suggestions such as being able to pause blocking sessions (“It would be useful if it had an option to pause or reset a session. I know this breaks the rules but it should be enough that we know that,” R865, Strict Workflow), and other times they complained that they were ‘not strict enough’ (“Too easy to bypass :( Will need to exercise a lot of self-control to stop myself from bypassing the timer,” R961, Strict Workflow, “I would like the ability to set a password to turn the block on or off,” R406, Block Site).

Similarly, for reward/punishment tools, users sometimes suggested increasing incentives for intended use (“would love if you could make it so you earned coins the longer the less tabs you had open and could buy things (hats,clothes, props, ect) with the coins,” R282, Tabagotchi), and other times they suggested decreasing them (“I hate the fact that we get a destroyed building … I feel like it is too punishing and almost says ‘you’ve failed’,” R883, SleepTown). Moreover, some users seemed to experience trouble when reaching the end of a reward scheme and wanted additional rewards to be added to keep the tool being useful to them (“realllllllllllly wish there were more than 3 phases to evolve into,” R582, Tabagotchi).

Some reviews implied that users were aware of multiple tools and had actively tried out options with different levels of friction to find one that worked for them (“I used to favor the hard approach of something like StayFocusd, but I’ve lately found that that can just create weird incentives and reinforce existing internal tensions. Intent helps me untangle my internal conflicts around my internet usage,” R405, Intent; “I bought Forest only to be disappointed because I thought I would like it more than Flora, but I ultimately didn’t because it takes a really long time to raise money and buy different trees. In Flora, everthing is fast and much more rewarding,” R174, Flora).

Finally, some users noted that the amount of effort involved in using the tool itself was important: a tool could become self-defeating if it was too demanding to use (“the reports are generated slowly to the point that i’m wasting time waiting for reports to generate. oh the irony,” R495, RescueTime for Chrome; “the application can further be improved by reducing the switching time (lag) between daily, weekly and monthly options,” R893, SPACE; “Would like a better way to block larger amounts of websites without much effort,” R754, Focus).

Theme 4: DSCTSs should adapt to personal definitions of ‘distraction’

Finally, tools needed to precisely capture the meaning of ‘distraction’ in the life of users to be helpful (n = 66, 7%), a theme often expressed in the form of feature suggestions.

One aspect involved getting tools to accurately capture what users defined as distraction (50% of reviews contributing to this theme). For example, feature suggestions sometimes involved being able to exempt particular apps from tracking or restriction as they did not represent something the user struggled to control (“I use apps on my phone to study, such a math app, a dictionary and my notes I store on my phone. I found that by trying to work on an essay, I was killing the plants,” R383, Flora; “I love the app, but I wish you could allow specific apps to run without affecting your phone usage time. For example, when I go on long walks I like to listen to YouTube playlists on my phone so it doesn’t let me turn the screen off. I won’t even look at my phone once, but while I’m on my walk it’ll be racking up hours of usage,” R665, QualityTime).

Another aspect involved getting tools to capture when specific activities counted as distractions (41%). For example, feature requests for tools aimed at curbing nightly use often involved being able to set different schedules for different days (“it needs to allow for the real life fact that people can’t go to bed and wake up at the same time everyday. If it was done on your amount of sleep you get in hours that would be better,” R659, SleepTown), and requests to blocking tools included allowing instances of use that did not represent distraction (“a peek feature, for quick access (maybe for 10 secs at most?) to ‘blocked’ websites, like Youtube, in case we need to change the song or skip something,” R283, Forest extension). A final aspect involved cross-device integration (17%): some users expressed a need to curb distractibility on all of their devices at once. Thus, some reviews said that tools on different devices needed to sync with one another to be truly useful (“I wish it worked more in-sync with the app - e.g if you start a tree in the browser, it would also grow the same tree on your phone,” R757, “Desperately needs to sync with the phone app so starting/failing on one starts/fails on the other,” R119, Forest extension).

4.4 Discussion

To sum up, our analysis of user numbers and ratings found that tools combining two or more types of design patterns received higher ratings than tools implementing a single type; reward features were the least common type in top tools, but present in tools with the very highest user numbers; and tools which included goal advancement features ranked higher on average ratings than on user numbers.

Our thematic analysis of user reviews found that DSCTs help people prioritise important but effortful tasks over guilty pleasures easily accessible on their devices (and are particularly useful for individuals for whom such self-control struggles are more difficult). Sometimes they do so by mitigating default designs that overload users with information. People seek out tools which provide a level of friction or reward that is ‘just right’ — a level which varies between people — for supporting intended behaviour without being overly restrictive or annoying, and they want tools to capture their personal definition of ‘distraction.’

We now turn to discussing implications of these results, in terms of how the landscape of tools provides commentary on common designs, and conceptual and practical implications for finding the ‘just right’ level of friction and capturing contextual meanings of ‘distraction.’

4.4.1 The landscape of DSCTs as commentary on default designs

The landscape of DSCTs available online provides a window into user needs and struggles in the face of common designs. The high average ratings given to these tools overall, as well as the content of user reviews, suggest that many people (at least among those that choose to try them out) find them very useful. Thus, tools on this market foreshadowed generic user needs that Google and Apple recently begun to address in the form of ‘Digital Wellbeing’ (Google) and ‘Screen Time’ (Apple) tools for monitoring and limiting device usage (cf. section 2.1.4). They also suggest specific design solutions, such as browser extensions that tackle information overload by hiding one’s email inbox until one makes a deliberate choice to see it (e.g., Inbox When Ready) or hiding Facebook’s newsfeed (e.g., Newsfeed Eradicator).

Comparing popularity metrics, our results suggest some potential disconnect between tools’ usefulness and how widespread they are. I speculate that our finding that tools which include goal advancement features rank higher on average ratings than on user numbers, and that some reward/punish tools rank at the very top of user numbers despite being rare, can be explained by how attention-grabbing they are: for example, scaffolding self-control using virtual trees that die if one’s device is used inappropriately might be more ‘sexy’ and likely to be shared with others than are tools which provide simple but useful reminders of the task one tries to focus on. This would match research on online virality which has found that content evoking high-arousal emotions are more likely to be shared (Berger and Milkman 2012; Pressgrove, McKeever, and Jang 2017), as well as findings in behaviour change research where strategies’ popularity and their efficiency often diverge (Kelly and Barker 2016). An implication is that whereas store metrics of popularity may provide useful clues about the utility of various design patterns, they should be used as a rough guide for subsequent controlled studies rather than taken as ‘ground truth’ (cf. Donald A. Norman 1999).

4.4.2 Self-control struggles and the ‘just right’ level of friction

Our finding that DSCTs are used when people focus on important but effortful tasks matches findings from research using other methods with, e.g., Tran et al. (2019)‘s recent interview study finding that engagement in tedious or effortful activities is a common trigger of compulsive smartphone use (also Reinecke and Hofmann 2016). Similarly, the search for tools that provide an optimal level of friction can be conceptualised as use of ’microboundaries’ (Cecchinato, Cox, and Bird 2017) and ‘design frictions’ (Cox et al. 2016) to promote goal-oriented engagement with digital technology, and aligns with wider research in personal informatics where, e.g., people planning for exercise try to set up a ‘sweet spot’ of contextual factors to succeed (Paruthi et al. 2018).

To understand the psychological mechanisms involved, the dual systems framework presented in Chapter 3 may provide a useful lens. To recap, according to this framework, behaviour results from internal competition between potential actions. Potential actions are activated either by automatic responses to internal and external cues (‘System 1’ control, e.g., checking one’s phone out of habit) or by conscious intentions (‘System 2’ control, e.g., taking out one’s phone because one has a conscious goal to text a friend). What wins out in behaviour is the action with the highest activation value, which may or may not be in alignment with one’s longer-term goals (e.g., checking one’s smartphone in a social situation out of habit despite having a goal to not do so).

From this perspective, DSCTs are used in situations where the internal struggle between potential actions are often not resolved in line with one’s enduringly valued conscious goals (cf. section 2.2.2). Users seek tools that provide a level of friction or motivation which biases this competition such that the actions that win out are in line with one’s longer-term goals — for example by using blocking tools to prevent unwanted System 1 responses from being triggered, by using goal advancement tools to remind oneself of one’s usage goals and thereby enable System 2 control, or by using reward/punish tools to provide extra incentives for System 2 control (cf. Chapter 3).

We suggest the finding that tools whose features combine more than one type of design pattern can usefully be interpreted through this lens: tools that combine two or more types of patterns (for example, a tool which does not simply remove Facebook’s newsfeed (block/removal), but replaces it with a todo list (goal advancement)) may be more likely to bias internal action competition sufficiently to cause a change in behaviour without being overly restrictive or annoying, than are tools which implement a single type. This may be because by combining design patterns that target different psychological mechanisms, each can be implemented at a more ‘gentle’ level of friction or intrusiveness while still in aggregate provide sufficient bias to the self-regulatory system to bring about an intended behaviour change. By contrast, tools focusing on a single design pattern targeting a single psychological mechanism may need to ramp up the level of friction more highly before sufficient impetus for behaviour change is provided — and in so doing is at greater risk of being perceived as annoying or ‘too strict’ by the average user.

For example, Forest combines growing of virtual trees with a countdown timer, which influences both the expected reward for control and sensitivity to delays, which seems to be effective, given this tool’s popularity with over 10 million users on Android alone. A version which simply grew virtual trees without a countdown timer might need to correspondingly increase the magnitude of reward to remain useful, but in doing so be more likely to be perceived as too forceful or manipulative (cf. M. K. Lee, Kiesler, and Forlizzi 2011).

4.4.3 The meaning of distraction

An important user need emerging from the reviews is that users look for digital self-control tools that capture their personal definitions of ‘distraction.’ We suggest that this has implications in two domains: customisation, and cross-device integration.

In terms of customisation, many tools received a combination of excited reviews from users who felt it matched their needs well, and reviews from less satisfied users who wanted specific features to be added to capture their situation (e.g., exempting particular apps or subdomain from being blocked, limiting weekly rather than daily usage, or setting custom schedules). For example, the Forest app on iOS (Seekrtech 2018), which rewards users for not using their smartphone at all during focus sessions, addresses the concerns of a student who considers all phone use while studying a distraction, but not those of a student who wants to access math apps. A conceptual implication is that studies of digital self-control tools should focus on assessing effects on people’s sense of using their devices in ways that align with their long-term goals, rather than on overall ‘screen time’ (cf. section 2.2). A design implication is that tools should include adequate controls for users to customise them to their needs or that the ecosystems of tools should be diverse enough for users to find tools that match their needs.

There may be a trade-off between customisation and friction in a single tool: providing more fine-grained control runs the risk of increasing the amount of effort involved in using the tool in the first place, which could undermine usefulness. Apple and Google may therefore be facing distinct challenges: Because Apple do not allow mobile developers the level of permissions required to implement proper usage logging and blocking tools (Digital Wellness Warriors 2018), only their own Screen Time app is capable of providing many basic features of DSCTs. This implies that this single app needs to be carefully designed to accommodate a wide range of user needs. Google, however, provide less restrictive permissions to developers, and an accordingly diverse range of potent DSCTs are therefore available on Android. Therefore, Google may face less pressure to ‘get it right’ with their own Digital Wellbeing tools, because less common user needs could be addressed by their app ecosystem.

In terms of cross-device integration, reviews suggested that tools should be sensitive to the overall affordances provided by the devices people use in combination. A research implication is that studies of digital self-control tools should move beyond considering a single device in isolation and towards studying the ecology of devices that people use, and what ‘distraction’ means in this context (cf. section 2.2). A design implication is that tools should be able to sync between devices, to accommodate a need to curb the availability of all digital distractions. This has been explored in two previous studies (cf. section 2.3.4) with, e.g., J. Kim, Cho, and Lee (2017) finding that multi-device blocking reduces amount of mental effort required to manage self-interruptions.

4.4.4 Limitations

Many user reviews provide little depth and may consist of only generic praise or critique, an angry bug report, be very short, or intend to paint a tool in a specific light for marketing purposes. Furthermore, we may not have an equal amount of data for all areas of the design space, and lack of reviews could represent poor marketing efforts or bad luck, rather than design ideas with low utility. Therefore, care must taken when interpreting evidence from user reviews and ratings (cf. Panichella et al. 2015).

In this chapter, we sampled reviews from top tools across the design space, similar to previous research (Roffarello and De Russis 2019a). The fact that our findings from reflexive thematic analysis resonated well with findings from studies using other methods such as surveys and interviews (Ko et al. 2015; Tran et al. 2019) suggest that this approach did provide valid evidence. However, future research may wish to leverage e.g. automated ways of identifying high-informative reviews in advance of thematic analysis (N. Chen et al. 2014; Panichella et al. 2015).

4.5 Conclusion

The landscape of DSCTs available online amounts to hundreds of thousands of natural ‘micro-experiments’ in supporting self-control over device use. As such, it provides a running commentary on user needs and struggles in the face of common design, as well as concrete suggestions for solutions. Therefore, studying characteristics of tools on this landscape represents a useful complementary approach to evaluating interventions in controlled studies, as the latter is difficult to scale to broad assessment of design patterns and implementations across the design space.

Extending Chapter 3‘s functionality analysis, this chapter investigated how design features relate to metrics of store popularity, as well as what user reviews reveal about digital self-control tools’ contexts of use and design challenges, using data from 334 tools on the Google Play, Chrome Web, and Apple App stores. Our findings raise new hypotheses and avenues of investigation, which may inform future prototype tools:

We found that tools which combine multiple types of design patterns received higher average ratings than do tools implementing a single type. A possible explanation is that targeting multiple psychological mechanisms makes it easier for a tool to encourage an intended behaviour change without being perceived by users as excessively restrictive or annoying. We also highlighted that user reviews express a need for tools to capture personal definitions of distraction and adapt to multi-device ecologies. This does not only resonate with current calls in related HCI research, but also raises practical implications for how major tech companies can deal with evolving user needs within the constraints they place on their app ecosystems.

Together with Chapter 3, the present chapter provides the first steps toward answering this thesis’ main research question of how existing digital self-control tools can help us identify effective design patterns, by reporting, at scale, how tools in online stores have explored the design space and how users have responded in ratings and reviews. In the next chapter, we turn our attention to how such investigations can drive targeted studies of promising design patterns.