6 Understanding Personal Digital Self-Control Struggles in the ‘Reducing Digital Distraction’ Workshop

6.1 Introduction

Many of the design patterns HCI researchers have developed to help people stay in control of digital device use have the potential to influence time spent overall and in specific apps (e.g., Kovacs et al. 2019; Kovacs, Wu, and Bernstein 2018), or help users feel more focused and in control (I. Kim et al. (2017); G. Mark, Czerwinski, and Iqbal (2018); see Chapter 2.3). However, existing studies also suggest that people’s goals for changing their patterns of device use tend to be more targeted and context-dependent than what is supported by current interventions. For example, a user might wish to reduce time spent browsing Facebook’s newsfeed, but increase time spent in specific groups on the platform. Such a goal is not easily met through interventions focused at the global or app level (cf. Hiniker et al. 2016). As a result, users are often ambivalent towards current digital self-control solutions — especially lock-out mechanisms — because they address only one need (preventing unwanted compulsive use) while interfering with positive use of their devices (J. Kim, Jung, et al. 2019; Tran et al. 2019).

In answering this thesis’ overarching research question (How can existing digital self-control tools help us identify effective design patterns for supporting self-control over digital device use?), the previous chapter focused in on what we might learn by investigating one specific approach among existing tools, namely browser extensions for self-control on Facebook. In the current chapter, we zoom back out to consider how the broader landscape of existing design patterns relate to people’s struggles and goals, and how we might reduce discrepancy. To this end, we report results of a series of ‘Reducing Digital Distraction’ (ReDD) workshops developed in collaboration with the University of Oxford Counselling Service. In these workshops, we investigated students’ struggles with controlling digital device use, and how they thought interventions drawn from recent reviews could help them achieve their usage goals. Similar to recent work taking a qualitative approach to studying ‘compulsive smartphone use’ (Tran et al. 2019), we took an active workshop approach to create a space for participants to engage in deeper reflection and discussion around their experienced struggles, what success might look like, and how specific interventions could help. In so doing, this study also adds to recent work that has sought to understand effective design patterns by actively supporting struggling users in finding effective solutions among current interventions (Cecchinato 2018; Kovacs 2019).

Our study was guided by the following research questions:

- RQ1: What do students consider ‘success’ at digital self-control?

- RQ2: How do students think existing interventions can help them achieve ‘success?’

- RQ3: How much do students’ preferences among interventions vary?

- RQ4: What directions for future work are suggested by the ways in which the workshops are practically useful?

We conducted four workshops with a total of 22 students, in which participants reflected on their struggles and goals in relation to digital device use, explored a selection of solution interventions, and committed to trying out the options they were most interested in. The included interventions related to distraction blocking, self-tracking, goal setting, reward or punishment, as well as more general customisation of digital environments. They were drawn from research presented in chapters 3, 4 and 5, as well as from interventions discussed on prominent tech blogs (Center for Humane Technology 2019; Knapp 2013).

We found that participants wished to continuously use their devices in line with their intentions, and divide up their use according to time of day and/or location. They felt digital self-control interventions were important to achieve this, because instant access to distractions on their devices, combined with what they saw as deliberately ‘addictive’ designs, routinely led them to use their devices for other purposes than what they intended and/or to excessively interrupt themselves. Participants were particularly interested in interventions that would remain effective when they were less motivated to control themselves — such as distraction blocking — but wanted such interventions to be precisely targeted rather than crude bans. For example, many wanted to try out interventions that would remove the newsfeed on Facebook, or video recommendations on YouTube, rather than block these services altogether. Finally, participants wished for tools that could serve as ‘training wheels’ for improving inner self-discipline over time. That is, they wished for tools they could use as external support initially, but which would later allow them to control themselves better in their absence. Responses from a two-month follow-up survey suggested that the workshops were effective at providing useful interventions for mitigating digital self-control struggles.

6.2 Motivation and background

While HCI researchers investigate possible interventions for supporting people’s ability to stay in control of their digital device use, many user groups face an immediate need for guidance, including families, students, and information workers (e.g., Aagaard 2015; A. L. Duckworth, Gendler, and Gross 2016; Gupta and Irwin 2016; Rosen, Mark Carrier, and Cheever 2013). Before we are able to provide such guidance on a solid basis, there are important questions that need further study (see section 2.4).

One question relates to what our design patterns should aim to achieve in the first place, such that their influence on behaviour and perception aligns with users’ goals (Lyngs et al. 2018; Munson et al. 2020). As we highlighted in section 2.2, much debate has focused on ‘screen time’ and ‘overuse’ (Dickson et al. 2019; Przybylski and Weinstein 2017), and many studies have accordingly investigated interventions designed to limit time spent on devices (e.g., J. Kim, Jung, et al. 2019; Ko et al. 2016, 2015). However, as smartphones, tablets, and laptops come to mediate an ever-expanding range of activities and contents—and platforms such as Facebook come to integrate a vast range of functionality— time on devices becomes a poor indicator of whether people’s use aligns with what they intended (Hiniker et al. 2019; Lukoff 2019; Orben and Przybylski 2019a; Orben, Etchells, and Przybylski 2018). Therefore, we may need to target interventions to just those aspects where users need support, to avoid interfering with digital experiences they value (see section 2.3.4).

Moreover, many users wish to make context-dependent changes according to time or space, such as spending more time in work-related apps when commuting (Hiniker et al. 2016), and may also find different interventions effective depending on their immediate emotional state (J. Kim, Cho, and Lee (2017); J. Kim, Jung, et al. (2019); Ryan et al. (2014); see section 2.3.4). These findings point to the need for a better understanding of how users understand ‘success’ at digital self-control and how we may design interventions that support their contextual needs.

Another question concerns the extent to which the interventions that are most helpful vary between individuals (see section 2.4.3). Previous studies have focused on mean effects in experimental study designs, but also reported that people often vary substantially in their preference for, and potential benefits derived from, specific interventions (J. Kim, Jung, et al. 2019; G. Mark, Czerwinski, and Iqbal 2018; J. Kim, Cho, and Lee 2017). For example, G. Mark, Czerwinski, and Iqbal (2018) found in an exploratory study with information workers that participants differed in their self-reported ability to control distractions, and that only those who reported being less in control at baseline benefited from blocking online distractions. Hence, we should investigate how much individual variation there is in users’ needs and preferences, and to what extent idiosyncratic needs can be met by current options.

Approach for this study

In keeping with the overarching research question of the present thesis, we may attempt to answer these questions by drawing on the existing landscape of digital self-control tools as resource for eliciting how people’s digital self-control needs are met by current interventions. Given the practical need for guidance, we may also consider collecting evidence by actively engaging with specific user groups in identifying effective solutions to struggles they face in their daily lives (cf. Hayes 2014, 2011; David C. Mohr, Riper, and Schueller 2018), as recent research has started to do. For example, the research project HabitLab broadly targets people who wish to reduce their time spent on specific websites or apps, and helps more than 12,000 daily Chrome and Android users meet their goals through interventions such as hiding content feeds or displaying timers (Kovacs 2019). Meanwhile, the platform allows researchers to study, e.g., the effectiveness of static vs rotating interventions (Kovacs, Wu, and Bernstein 2018), or ‘spill over’ effects from one distraction to another (Kovacs et al. 2019). Another project conducted workshops with information workers in which they discussed challenges and ideal scenarios around work-life balance and digital device use and committed to trying out specific solutions (Cecchinato 2018). These workshops helped participants in the form of concrete interventions and support to follow through on their commitments, while generating research data through workshop recordings as well as follow-up interviews and surveys.

In this chapter, we draw on the range of digital self-control interventions reviewed in chapters 3, 4, and 5, while building on the active research approaches of recent projects, to advance our understanding of contextualised, personal digital self-control struggles and appropriate interventions. We collaborated with the University of Oxford Counselling Service, who work one-on-one with nearly 3,000 students each year, in developing a workshop that would serve as a local intervention for students struggling to manage their relationship with digital technology (Lyngs, Lukoff, Slovak, Freed, et al. 2020). While numerous studies have highlighted these struggles among students (e.g., Aagaard 2015; Gupta and Irwin 2016; Rosen, Mark Carrier, and Cheever 2013), the work presented in this chapter is the first to focus on this demographic in a workshop intervention that embeds design patterns drawn from comprehensive reviews of existing digital self-control tools.

6.3 Methods

The workshop materials are available via the Open Science Framework on osf.io/hdvtm/.

6.3.1 Recruitment

Between May 2019 and March 2020, we conducted four workshops at the colleges of Merton, Corpus Christi, New, and St John’s at the University of Oxford. The workshops were advertised with posters and mailouts distributed by student support administrators at the colleges, and broadly targeted students struggling with digital technology use (see Appendix B for an example of a recruitment poster). Sample content from recruitment emails include:

Ever deleted Facebook only to come back on? Is Instagram driving you crazy? Do you have a love/hate relationship with your smartphone? Are there too many tabs open in your brain?

If so, please come to a new “Reduce Digital Distraction” workshop developed by Computer Science DPhil student Ulrik Lyngs in collaboration with Maureen Freed from the University Counselling Service. This two-hour workshop will encourage some creative reflection on your digital life — what works and what doesn’t — and will provide you with support to make real, practical changes for a happier, healthier digital life.

Interested students were directed to get in touch via email to reserve a space. There were no restrictions on who could take part among those who expressed interest.

6.3.2 Materials

Tools and interventions presentation

A brief presentation introduced participants to the landscape of existing digital self-control tools and interventions, grouped into five types with representative examples:

- Block or remove distractions (e.g., blocking distracting websites or removing Facebook’s newsfeed)

- Track yourself (e.g., tracking and visualising laptop use)

- Advance your goals (e.g., replacing Facebook’s newsfeed with a to-do list to remind users of their goals)

- Reward or punish yourself (e.g., growing virtual trees that die if one’s smartphone is used during a focus session)

- Change your digital environment (e.g., rearranging the positioning of apps such that distracting options are harder to access).

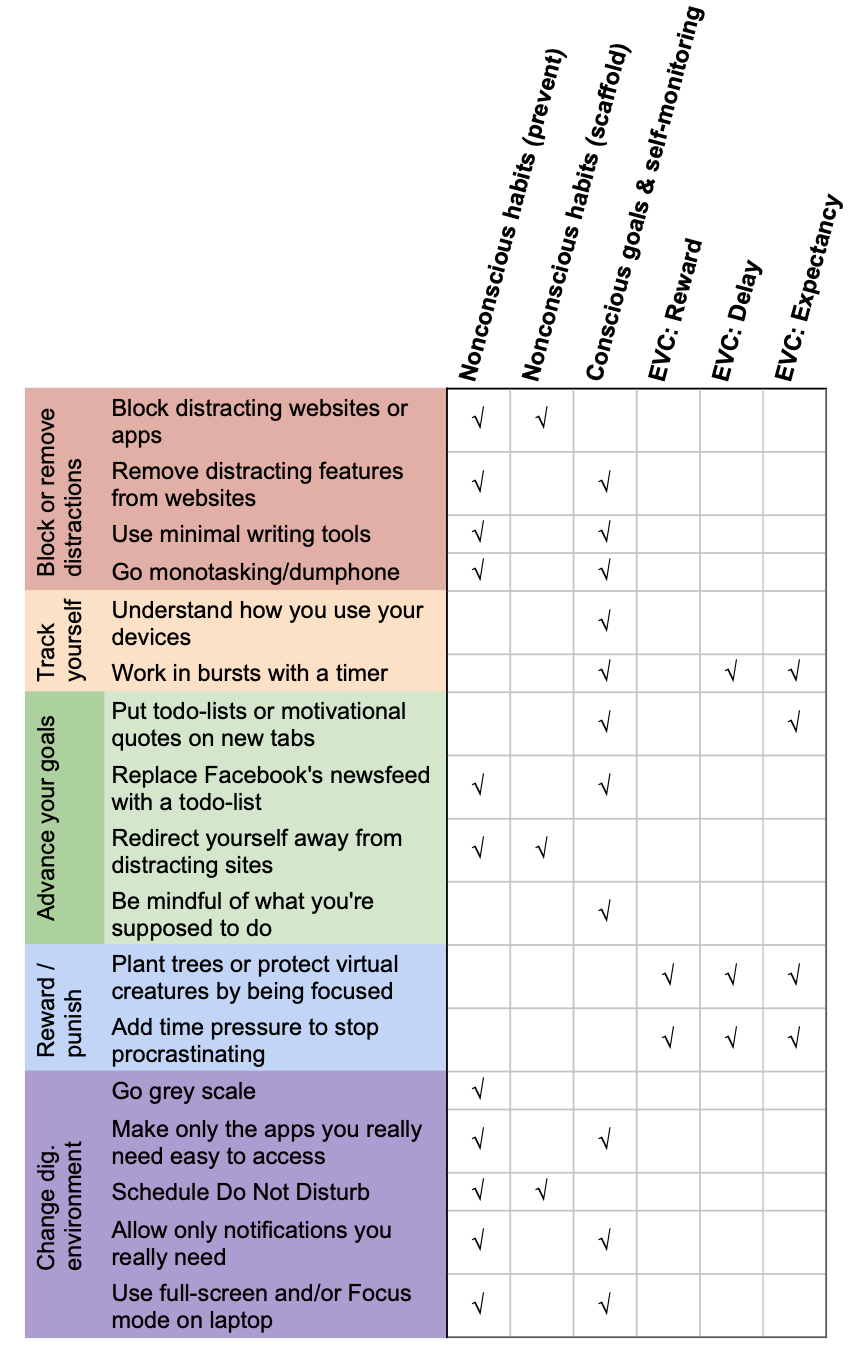

The first four categories were drawn from research presented in chapters 3, 4 and 5, whereas the fifth was based on interventions discussed on popular tech blogs (e.g., Center for Humane Technology 2019; Knapp 2013). We condensed the diversity of design patterns and implementations within these five types into 17 categories based on what we judged to be an accurate summary of the main approaches explored within these types (see Figure 6.2; cf. chapters 3, 4 and 5).

Figure 6.1: Mapping digital self-control interventions included in the Reducing Digital Distraction Workshop to cognitive mechanisms in the dual systems framework.

From a dual systems perspective, the psychological mechanisms targeted by the 17 categories depend somewhat on the implementation details of a specific intervention; for example, an extension for blocking specific websites may also display motivational quotes. However, based on Chapter 3’s guidelines for mapping design patterns to main components in the dual systems framework (see section 3.3.2.4), we view the psychological mechanisms that each intervention has the most immediate potential to influence as shown in Figure 6.1.10 All mechanisms were covered by the interventions included, albeit with a frequency that mirrors the current balance in how existing DSCTs have explored the design space (cf. section 3.3.2.4).

Card sorting

Figure 6.2: Intervention cards

Figure 6.3: Card sorting background

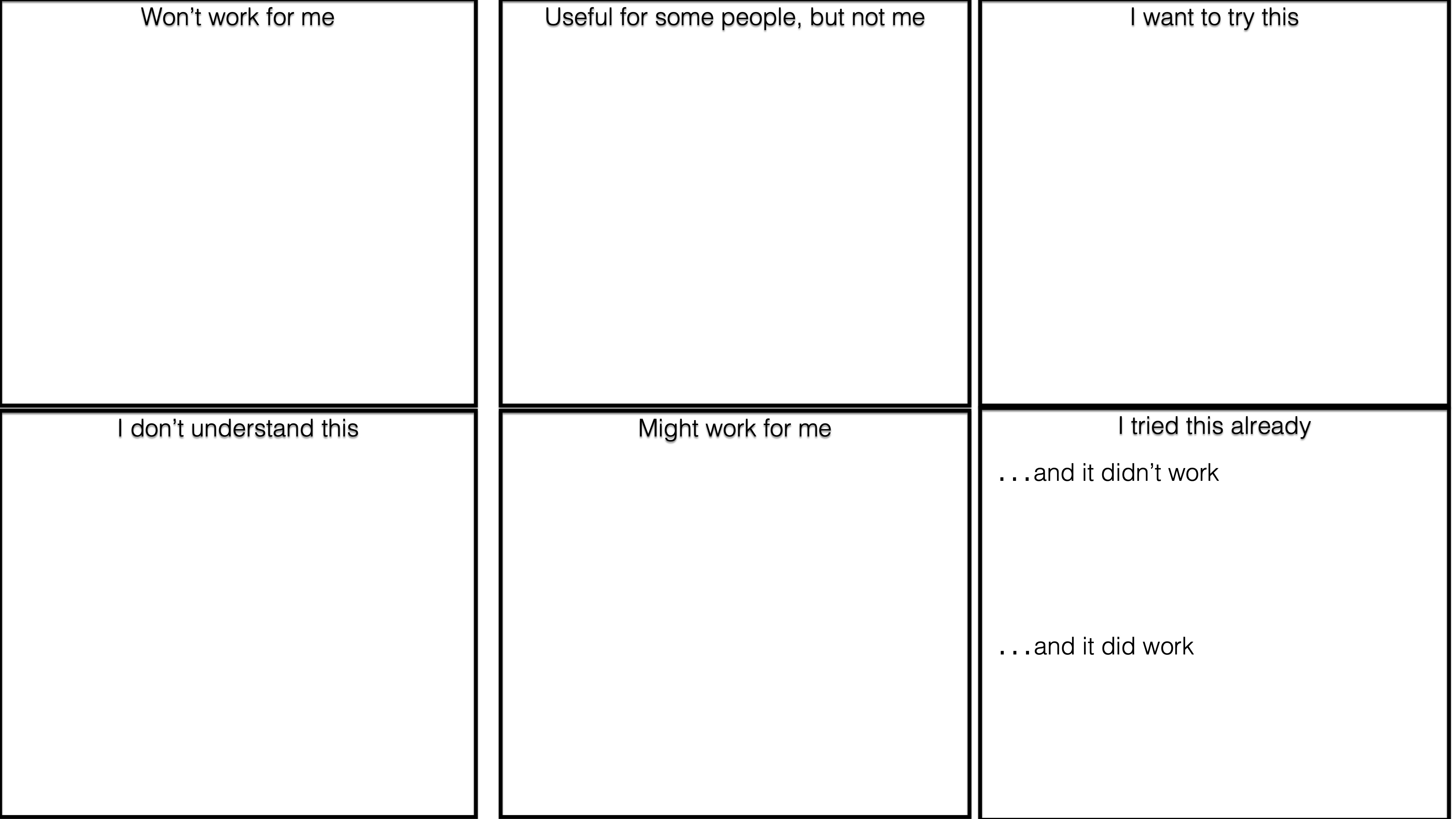

To help elicit information about how applicable and useful participants expected the interventions to be, we used card sorting, a common knowledge elicitation method in user experience design (Martin and Hanington 2012; Spencer 2009). Specifically, we used a ‘closed card sort,’ in which we gave each participant a set of cards plus a set of pre-determined categories, and asked them to sort cards into categories as they saw fit. Each participant was given a set of 17 cards, which each represented a specific intervention with a caption and one or two screenshots (all cards are shown in Figure 6.2). Each card also had a heading that classified it within one of the five main types.

Participants sorted cards into the categories ‘I don’t understand this,’ ‘Won’t work for me,’ ‘Useful for some people, but not me,’ ‘Might work for me,’ ‘I want to try this,’ and ‘I already tried this and it did/didn’t work’ (Figure 6.3)11. Each card had a QR code pointing to the workshop website (see below). Cards were printed in colour on thick paper in size A6, and sorted into categories on a white A2 paper sheet.

Workshop website

To provide participants with details and implementation instructions for the interventions, we developed an accompanying website. The website contained separate pages for each type of intervention, with tabs for the specific interventions within that type. Each tab in turn contained descriptions, screenshots, and links to the key implementation options available on laptop, Android, and/or iOS.

When many options were available for implementing an intervention, we chose tools to include based on which had the highest user numbers and average ratings on the corresponding app or browser extension store. Where available, we also included options that did not require participants to install additional software (e.g., when interventions were available via Android’s ‘Digital Wellbeing’ or iOS’ ‘ScreenTime’ features). In total, the website contained descriptions and pointers to 47 options across the 17 intervention cards. Descriptions and mapping of all options to dual systems theory is available via the Open Science Framework on osf.io/ed3wh/

The website was generated from an R Markdown source file and deployed via GitHub Pages on ulyngs.github.io/reducing-digital-distraction/. QR codes on the intervention cards pointed to the corresponding section of the website.

Two-month follow-up survey

In the follow-up survey, participants rated each workshop component on a 5-point Likert scale (‘Not at all useful’ to ‘Extremely useful’), with an additional ‘I don’t remember this part’ response option. Afterwards, they answered questions about whether they followed through on the intervention/s they committed to, and whether they had been useful. The survey ended with feedback on the workshop format and website, and was built and administered using Jisc Online surveys. Survey items and layout is available in the supplementary materials.

6.3.3 Procedure

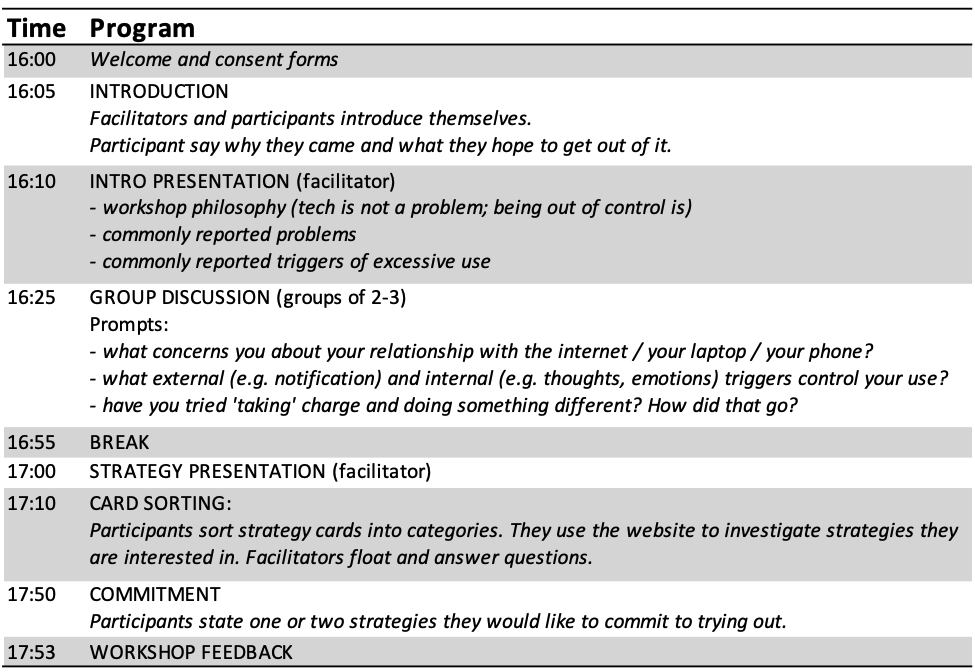

Figure 6.4: Workshop procedure

A workshop lasts about 2 hours and is divided into two parts (see Table 6.4).

First half

Upon arrival, participants sign consent forms. The facilitator(s) introduce themselves, and ask the participants to each share why they signed up to the workshop and what they expect to gain. Then, the facilitator(s) present the workshop aims, along with introductory remarks on commonly reported struggles and triggers for problematic use of digital technology. Following this, participants are split into small groups (2-4 participants), with the facilitator(s) moving between groups. In these groups, participants engage in open-ended discussion prompted by the questions (i) what concerns you about your relationship with the internet / your laptop / your phone?, (ii) what external and internal triggers control your use?, (iii) have you tried ‘taking charge’ and doing something different? How did that go?

Second half

After a break, a facilitator gives a brief presentation on interventions and tools for digital self-control, and introduces the card sorting task. After participants finish sorting cards, they investigate the interventions they are most curious to try out, with guidance from the website and the workshop facilitator(s). A facilitator circulates and records how participants sorted the interventions and asks them to provide any comments they have on why they sorted the way they did. Finally, participants commit to trying out one or two interventions. The workshop ends with brief verbal participant feedback on the workshop.

Commitment reminder & follow-up survey

One week after the workshop, participants are sent an email reminding them of the intervention/s they committed to trying out, alongside a link to details on the website. Two months after the workshop, they are sent a link to the follow-up survey described earlier.

6.3.4 Analysis

A collaborator (Kai Lukoff) and myself transcribed all workshop recordings. Subsequently, I conducted inductive thematic analysis of the qualitative data following the ‘reflexive’ approach described in (V. Braun and Clarke 2006) and (Virginia Braun et al. 2018). First, I read all transcriptions and free text survey responses and conducted initial coding of recurrent patterns relevant to our research questions. Afterwards, I read through all coded excerpts, recoded instances, iteratively sorted the codes into potential themes, and discussed emerging themes with two collaborators (Kai Lukoff and Petr Slovak).

As noted above, the sorting categories ‘I already tried this and it did/didn’t work’ were added only after the third workshop. For the card sorting from the first workshops, if participants explicitly said in the video recording of their sorting that they had already tried a given intervention, and that it did or did not help them, we coded cards as placed in one of the corresponding categories, even though these categories were not available to them at the time of the workshop.

The thematic analysis was conducted in the Dedoose software; quantitative analyses were conducted in R.

6.4 Results

22 participants (9 women) took part across four workshops; 5 in the first (May 2019), 4 in the second (June 2019), 5 in the third (November 2019), and 8 in the fourth (March 2020).

6.4.1 Participants’ overall device use and self-control struggles

Digital devices played an essential role in participants’ lives, with laptops and smartphones mediating or interspersing all their daily activities. However, they struggled to control their use, mostly in relation to social media, email, and specific web content such as sports or news sites. In particular, more than half highlighted Facebook as one of their main challenges, which was related to the central role of this platform in coordinating university-related activities where “everything here seems to be on Facebook and Facebook Messenger so that one site is pretty much everything, it’s your connection to your whole Oxford community” (P5).

In terms of devices, some participants said they struggled mostly with controlling their smartphone use, as “when I’m on my computer I’m already quite focused” (P17). Many others struggled equally on their smartphone and computer. No participants mentioned struggles in relation to other digital devices than smartphones and computers.

Their struggles mainly involved going to their devices and digital services with a specific intention in mind, but then getting distracted from their intention and doing something else, and/or excessively interrupting themselves:

“I get the phone to do X and… yeah I think it erodes me to, like, I read several articles and then check my Facebook and WhatsApp and Instagram and then put the phone away and [then] I am like ‘oh shit’” (P3)

“I often will go to check something and then before I go to, like, click on the necessary group or the necessary message I’m always scrolling and like I forgot what I was looking for” (P4)

“I’ll like constantly keep checking as a sort of mini-break” (P7)

Most participants’ struggles were ‘self-control dilemmas,’ in that they struggled to stay focused on a task when more immediate gratification was available from doing other things on their devices. These struggles were driven by impulses or habits that conflicted with their better wishes (“I know I shouldn’t do it […] it’s just that there is this urge to check your phone”, P3; “sometimes I just get my phone without even the desire to use it […] I was like ‘what are you doing?’” P1), or by a desire to escape from uncomfortable feelings when they worked on tasks that were effortful or boring (“the second there is that academic intellectual pain then I […] move immediately to the digital media” P9). Some participants said their struggles were more about prioritising between multiple tasks that were all seen as important, particularly tasks involving social responsibilities:

“[My] self-control is kind of okay, I don’t get super distracted […] my biggest challenge is splitting priorities, so if I go in to do academic work, like welfare or JCR stuff, or something on Facebook or I’m in a conversation with someone […] I feel if I don’t answer those emails in that minute, or if I don’t answer that message, something later on in the week, or the month, or that day won’t happen” (P1).

In addition, participants said it was more difficult for them to stay in control the more unstructured their schedules were. Thus, several participants emphasised that their loosely structured student life — where their accommodations generally functioned as “an all-purpose place” (P7) for both personal and work activities — made it particularly challenging to find effective interventions for managing use:

“When I was working […] I could set hours, I could set expectations and it felt like the divide between my personal life and my working life was very clear, whereas here I think it’s very difficult because they are very enmeshed and like everyone knows you’re here just for this… and so it doesn’t feel like you can draw a clear divide” (P6)

Similarly, many participants said it was especially difficult to stay in control when they were working on tasks that did not have a clear goal: “I find it quite easy to stay focused on basic like simple tasks […] because there’s a clear goal whereas thinking something through, thinking through and developing ideas I think it’s easier to go off track” (P15).

Finally, participants emphasised that social expectations around acceptable use in their immediate surroundings had an important influence, as “I don’t generally have problems when I’ve got people to interact with or something to do it’s more… idle moments when you’re by yourself that it really encroaches on my time” (P1). Depending on the situation, this could work both for (“if I work in a big open public library, the RadCam, you get sort of shamed into like… you feel so exposed if you go on Facebook” P12) and against their ability to stay in control (“you walk into any given library and there will be a couple of people with Facebook out on their laptop at any time so it’s kind of like, ‘oh yeah it’s okay if everyone does it’” P1).

These struggles left participants frustrated, because they wasted time (an instance of self-interruption or diversion often led to a spiral of further distraction), had their workflow interrupted, or missed out on sleep when they got distracted at bedtime. They were worried about compounding negative effects on their mental well-being, partly because “it never really gives me a break… there’s like this background noise the whole time” (P1).

6.4.2 Participants’ views of ‘success’ and the role of digital self-control interventions

We developed three themes through our analysis in relation to what participants considered to be ‘success’ for their digital device use and how they thought current digital self-control interventions might help: First, success as intentional use that is divided up according to time and location; second, digital self-control as ‘training wheels’ for self-discipline, and finally overcoming low motivation through targeted blocking rather than blanket bans.

6.4.2.1 Success as intentional use that is divided up according to time and location

No participants viewed success as getting off their devices altogether. Rather they wished to be more in control and use them purposefully and actively in line with their intentions, as opposed to merely out of habit or in response to momentary urges (e.g., to escape boredom). “Every time I use my phone I’d like to do the thing that I intended to do and then leave it there […] times when it’s not so great is when I am purely passive” (P1). Some highlighted that they already felt in control over much of the functionality on their devices — “music and podcasts […] I don’t really have a problem with that” (P20) — and wished that they were similarly able to control their use of, e.g., social media.

When probed for specific implications of being in control, most participants said they wanted to ‘timebox’ better such that they would use their devices for certain things only at certain times and free up longer stretches of uninterrupted time:

“Success for me looks like being able to ‘partition’ in the sense of having a designated time to look at social media and emails and to deal with it and then for the rest of the day not.” (P7)

“Like wake up, pack up, check it over breakfast, then don’t look at it for 4 hours.” (P18)

“If I’m gonna work I’m just going to work […] I don’t think I aim too high, really” (P5)

Many also wanted to divide up their device use according to physical space, and for example not use smartphones in the bedroom. Some already tried to control their use in this way by making location-based rules for themselves such as “phones don’t go upstairs in my house” (P6), by leaving their smartphone behind when going to the library to study, or by charging their phone in another room than their bedroom.

By using their devices in a more purposeful manner that was partitioned in time and place, they hoped that their use would feel more worthwhile and add enduring value beyond the individual instance of use:

“[Success is] using it productively and you don’t feel like after you’ve used them for a number of hours that you’ve wasted your time, like you can actually remember what you’ve used them for and not just scrolling through […] if you’re kind of like actually concentrating on what you’re looking at then I think it’s probably worthwhile” (P13)

6.4.2.2 Digital self-control tools as training wheels for self-discipline

To achieve their usage goals, participants felt they needed to find the right digital self-control interventions. The allure of instant access to huge amounts of functionality on their devices, combined with deliberately addictive designs, was stronger than their willpower:

“It’s easy to get a little bit pessimistic about just how good my self-discipline can really be, given that I know that there’s like a billion-dollar economy in making sure that I am as addicted as possible” (P20).

“I know I won’t be able to control it once I open an app, you just will go down a rabbit hole… so I just, I understand that it’s more like treating an alcoholic, like it’s better to avoid it.” (P3)

Whereas several participants had found that simply putting their digital devices away therefore tended to be the most effective intervention, this approach failed when they had to use the devices that distracted them: “I tried locking my phone away while I’m doing my work but in practice everything I would do on my phone I can also do on my laptop so […] I don’t think it makes actually that much difference” (P20). Therefore, participants were keen to explore more technology-based solutions.

Importantly, many participants wanted such solutions to act as ‘training wheels’ for supporting their self-discipline rather than simply solve the problem for them and leave them vulnerable in their absence. For example, one participant said in response to the interventions presented in the workshops that they were “treating the symptoms rather than dealing with the actual problem”, as what he ideally wanted was to control his use only via “self-discipline,” but then admitted “I haven’t figured out a way to deal with the actual problem so like any solutions that can begin to [help] are good solutions” (P18). Echoing the same sentiment, another participant hoped that specific interventions could function as stepping stones to improve his self-discipline:

"In an ideal world I’d like to be able to do that without the need for artificial tools that sort of make me do it… using the apps that block websites for extended periods of time then sort of work my way off of those with time to just do it via self-control" (P4)

Thus, participants seemed to identify being in control via ‘self-discipline’ with controlling themselves via their own inner resources as distinct from using external interventions to, e.g., block or remove distractions or provide rewards.

Similarly, some participants were reluctant to consider tools or interventions they felt were infantilising: “Things that actually limit your [use] feel soooooo condescending… I’m a grown human I should be able to not check my email 57 times a day.” (P6) It therefore seemed important to our participants that design patterns were implemented in a way that would support and respect their sense of autonomy. Whether specific interventions were perceived as condescending varied substantially between participants, which one participant suggested was influenced by age: “I think I’m more open, I’ve only really sort of rejected three [interventions]… I suppose being beyond the age of adolescence I don’t mind as much the authority figure.” (P9)

6.4.2.3 Overcoming low motivation through targeted blocking rather than blanket bans

Participants highlighted that whether a specific intervention would be useful depended on their mental state. Some participants had found that simple, manual interventions like setting a timer and resolving to not use their phone for some period could be surprisingly effective (“By the time the 15 minutes have ended I would be like into my work enough that I wouldn’t have an urge to go back to my phone”, P8), but the challenge for such interventions was that they required them to be in a psychological state where a certain level of control was available in the first place:

"There has to be like a base level of self-control to initiate that process, like I’ve got to be in that sort of mindset… I think that applies for most of the things I’ve tried, having that sort of, you wanting to do it in the first place and I don’t necessarily want to." (P4)

Therefore, many participants were interested in exploring interventions for “removing choice or agency” (P12), such as blocking distracting websites or apps, which they expected to be more helpful in the situations where they really struggled. However, several participants emphasised that such interventions needed to be precisely targeted:

“More forceful measures is basically the way forward I think for me because… even with things that block distractions I have to use them in order for them to work so I think it’s more helpful to have things that either just keep me on one thing or keep me off other things and it matters that those things are erm as specific as possible as opposed to a blanket kind of ban” (P16)

More ‘specific’ interventions would be targeted to just the elements they struggled to control. For example, in relation to Facebook many participants were interested in interventions that would remove the newsfeed or replace it with a to-do list, which might help them “[use] it in a more focused way rather than completely blocking it out” (P1) and therefore be more useful given the many uses they had for this platform. This approach appealed to many because it intervened only on “an element of Facebook that directs my attention in a way that’s not the way I want it to go” (P21), without restricting them in relation to elements they did not struggle with. This intervention did, however, mean that they then had to find specific solutions for each distraction: “[removing Facebook’s newsfeed] that’s been helpful for me but that’s one… the problem is that’s one app that’s one platform, right? so that wouldn’t work on Twitter” (P21).

6.4.3 Individual variation

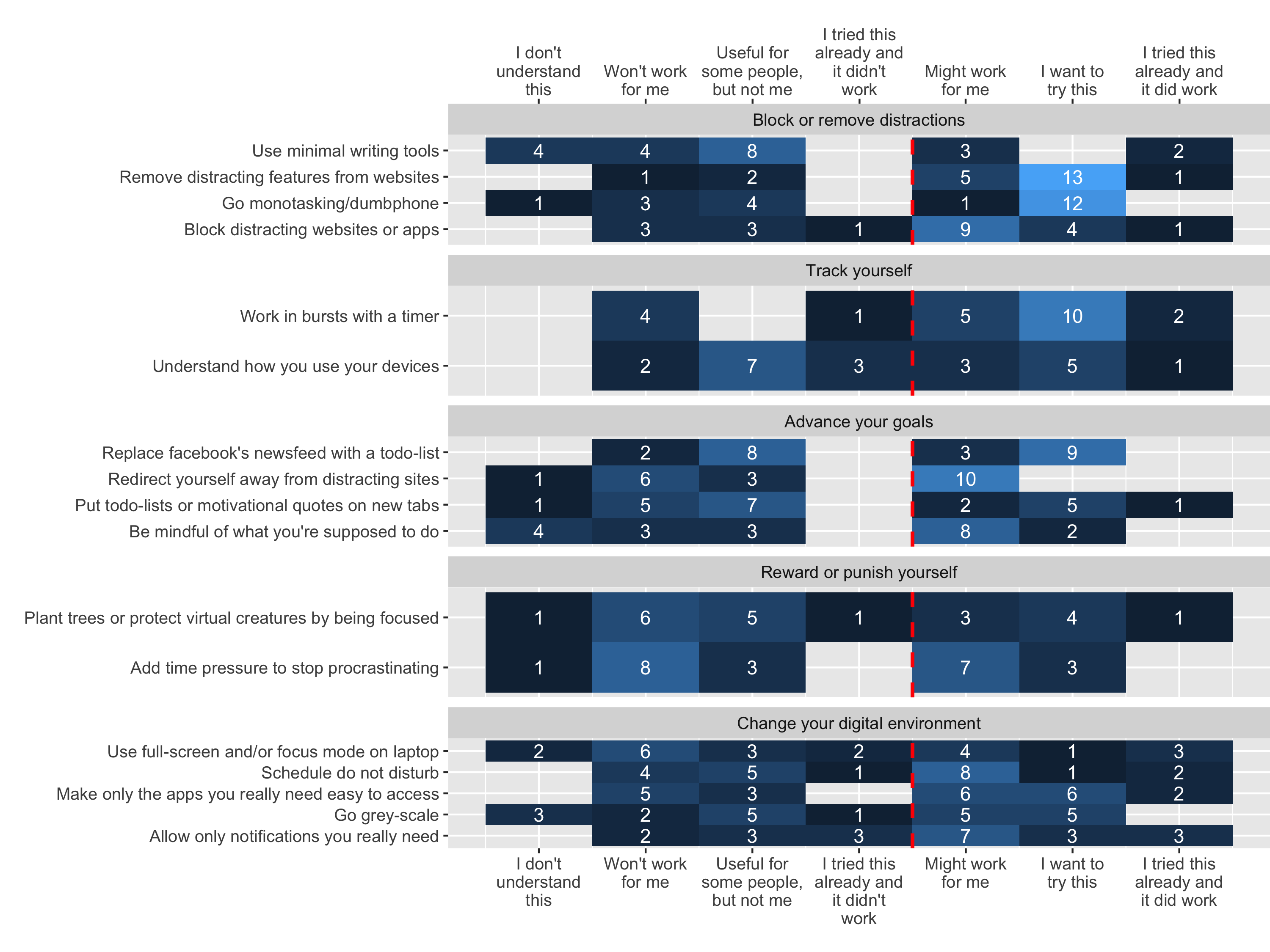

Figure 6.5: The number of times each intervention card was sorted into each category. The red dotted line separates categories suggesting rejection vs. acceptance as possibly useful. Note that the categories ‘I tried this already and it did/didn’t work’ were added only after workshop three. Even though these categories were not available at the first workshops, if participants explicitly said in the workshop that they had already tried a given intervention, and that it did or did not help them, we coded cards in the corresponding category.

The qualitative data suggested a substantial degree of variation in participants’ preferences among the interventions. For example, this was illustrated by the contrast between participants who were interested in blocking solutions and those who found this approach patronising, or between those who liked the gamification approach of Forest and those who found it plain silly:

“I have that tree-growing app, that’s quite good cause it makes me feel good and safe” (P13)

“it’s a bit ridiculous […] the more I think about the plant the more kind of… funny it feels, I don’t know how seriously I would be motivated by a tree […] I could just have done that with a timer” (P10)

Keeping the limited sample size in mind, participants’ sorting of the interventions supported this picture (Figure 6.5): About half of all interventions (9 out of 17) were roughly equally likely (40-60%) to be placed in an ‘accept’ (‘Might work for me,’ ‘I want to try this,’ or ‘I tried this already and it did work’) as in a ‘reject’ (‘Won’t work for me,’ ‘Useful for some people, but not me,’ or ‘I tried this already and it didn’t work’) category. The card sorting also suggested that a few interventions were especially likely to be found useful: specifically, the two interventions ‘Remove distracting features from websites’ and ‘Work in bursts with a timer’ were placed in an ‘accept’ category by more than three quarters of participants.

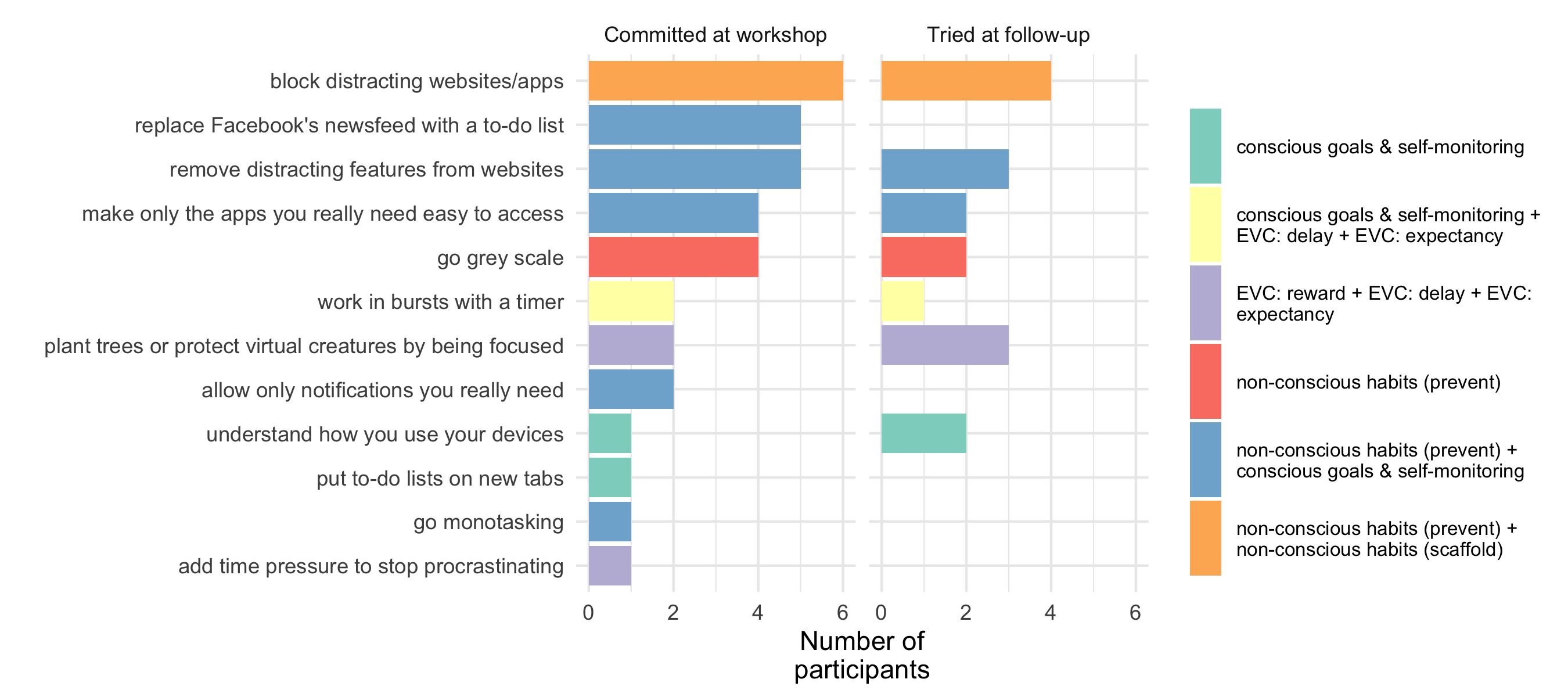

Figure 6.6: The interventions that participants committed to trying out in the workshop, and which ones respondents at the two-month follow-up had actually tried. Fill colour show intervention mapping to dual systems theory.

When committing to specific options, participants on average chose 1.5 interventions (min = 1, max = 3, Figure 8), spread across 12 of the 17 options. The top three interventions were ‘Blocking distracting websites/apps,’ ‘Remove Facebook’s newsfeed with a to-do list,’ and ‘Remove distracting features from websites’ which all involved removing agency or habit triggers. No participants committed to the interventions ‘Be mindful of what you’re supposed to do,’ ‘Redirect yourself away from distracting sites,’ ‘Use minimal writing tools,’ ‘Schedule Do Not Disturb,’ or ‘Use full-screen and/or Focus mode on laptop.’

6.4.4 Workshop usefulness

50% of participants (n = 11) filled in the two-month follow-up survey.

When converting participants’ ratings of the usefulness of each workshop component to numeric values from 1 (“Not at all useful”) to 5 (“Extremely useful”), the mean rating for the initial presentation as well as for the card sorting task was 3.3 (SD = 0.6 for the initial presentation, SD = 1.0 for the card sorting), the group discussion 3.4 (SD = 0.8), the website 3.9 (SD = 0.9), and the tool presentation 4.0 (SD = 0.8). No components received any ‘Not at all useful’ responses.

10 out of 11 respondents said they followed through on the interventions they committed to, 8 out of 10 found them useful, 7 out of these 8 still used them, and all respondents said they had noticed changes in how they managed digital distraction after the workshop. The interest in targeted blocking that participants expressed in the workshop was supported by the reported experiences of all three respondents who tried removing the newsfeed from Facebook and/or recommended videos from YouTube, all of which were positive (e.g. “[It] completely changed the way I used Facebook and YouTube. I waste a lot less time on both, but still have the functionality when I want it”).

Respondents’ experiences also suggested that they benefited from exploring multiple interventions, as a couple of respondents noted that only one of the options they tried were useful (e.g. “Restructuring my apps had very little impact […] However, I did find that setting time limits on my apps made me stop to think about why I had accessed an app and if I really needed to use it”).

Other themes in respondents’ free text responses related to heightened awareness of their patterns of device use (n = 4, “Even when I do allow myself to get distracted, I’m more aware of the fact that I’m getting distracted and have been working more mindfully to stop myself”, respondent tried the ‘Block Site’ browser extension to block distracting websites plus a pomodoro timer), reduced time on digital distractions (n = 3, “I’ve noticed that I spend less time on certain apps (notably facebook), although this is still ideally more than I’d like to”, respondent tried rearranging apps plus setting time limits) and avoided use of distracting services (n = 2, “I deleted Instagram”, respondent tried an unspecified time tracker plus the Forest app).

6.5 Discussion

Through a workshop for helping address struggles with digital distraction, we examined what university students considered success for digital device use and how they thought digital self-control interventions might help. In a student life with constant digital connectivity and little separation between work time and personal time, participants struggled with being distracted from their intentions during device use, and with excessively interrupting themselves. They wished to be able to use devices more in line with their intentions (as opposed to merely out of habit or to escape uncomfortable feelings) and divide up their use according to time and location. To achieve this, they felt digital self-control interventions were necessary because the easy access to digital distractions and the ‘addictive’ designs of their devices meant they were up against forces stronger than their willpower. Participants’ preferences between interventions were varied. However, they were particularly interested in interventions that ‘removed agency,’ especially when targeted to specific distracting elements (e.g., removing Facebook’s newsfeed) instead of blocking apps or sites altogether. Finally, participants said that what they really wanted was interventions that over time would help them stay in control using just their inner self-discipline without need for external support.

In the following, we first discuss research implications of these findings before outlining some of the limitations and future work.

6.5.1 Moving closer to accommodating contextual needs via targeted, within-app interventions

The participants highlighted the crucial role of contextual factors in relation to their needs for digital self-control interventions. One broader factor that made it difficult for them to stay in control over their device use was lack of boundaries between work and personal life (Cecchinato 2018), as they felt unable to set clear working hours and expectations of availability and needed to use Facebook for social as well as academic communication. They also described specific situational factors related to their immediate task and mental state, including that control was more difficult when working on tasks that had loosely defined goals, or which were effortful or boring, or when they were otherwise low in motivation (Ryan et al. 2014). Whereas many participants thought simple, manual interventions like productivity timers would be useful, these situational factors raised a need for interventions that removed some of their agency and would remain effective in the face of low control motivation (‘commitment devices’ (Willigenburg and Delaere 2005)). How might we be able to provide such interventions without interfering with positive device use (J. Kim, Jung, et al. 2019)?

A couple of recent studies of interventions that lock the user out of their devices or block online distractions have attempted to make such interventions more useful by incorporating location-based reminders (I. Kim et al. 2017), or by automatically blocking distractions at break-to-work transitions (Tseng et al. 2019) or when the user is sedentary and not using their device (which might imply that they are studying (I. Kim, Lee, and Cha 2018)). In addition to such approaches, our study suggest that we investigate interventions that intervene specifically on interface elements that make it difficult for people to stay in control (cf. Chapter 5). The vast majority of existing digital self-control studies have focused on interventions that monitor or block device use at a global or app level. Little attention has been given to interventions that simply remove or redesign specific elements within a problematic app (see Lottridge et al. (2012) and Chapter 5 for exceptions). In our study, participants showed a strong interest in browser extensions that adjusted specific elements of frequently used services, namely removing Facebook’s newsfeed or replacing it with a to-do list, as well as removing video recommendations on YouTube. As outlined in this thesis, hundreds of browser extensions that address self-control struggles in this way are available in online stores, and the research presented in Chapter 5 agrees with the present study that they can support people in meeting their goals with less collateral damage to positive use than global or app-level interventions.

6.5.2 Designing interventions to support self-discipline

A complementary research implication relates to participants’ wish for digital self-control interventions that function as ‘training wheels’ to improve self-discipline. Such interventions would help participants work themselves up to being in control with less external support in the future. Approaches to addressing self-regulation struggles with this aim have long been studied in social-emotional learning (Slovak, Frauenberger, and Fitzpatrick 2017), but no existing digital self-control studies have investigated how interventions might make themselves superfluous over time. One way to clarify what this might mean, and consider if it is a sensible design goal, is by exploring the idea from a psychological perspective. Whereas training people on tasks that require conscious control does not by itself translate into general improvement (Friese et al. 2017; Lurquin and Miyake 2017; Miles et al. 2016), our dual systems framework (Chapter 3) does suggest a few plausible routes by which design patterns could improve self-discipline over time:

First, as has already been suggested in digital behaviour change intervention research (Pinder et al. 2018), we may build tools that support people in acquiring automatic habits that are aligned with the way in which they wish to use their devices. Existing research, as well as findings from our workshops, shows a central role of unwanted habits in digital self-control struggles (e.g., Oulasvirta et al. 2012; J. Kim, Cho, and Lee 2017). Yet, existing studies of design patterns for digital self-control have rarely focused on their potential to support beneficial habit formation over time. Chapter 5‘s study of supporting self-control on Facebook via either removing the newsfeed or adding goal prompts and reminders suggested some habit-formation effects: participants reported lower interest in the newsfeed or an enduring habit of asking themselves about their purpose of use, respectively, when the interventions were removed after a two-week intervention period. To investigate the potential to support self-discipline via habit formation, we should explicitly evaluate how effects persist after an intervention is removed, and how habit formation might be ’boosted’ or sustained by varying when and how interventions are applied (K. J. Miller, Shenhav, and Ludvig 2019; Kovacs, Wu, and Bernstein 2018).

Second, we may design to support people’s confidence in their own ability to control their device use. This would focus on the ‘expectancy’ component of the Expected Value of Control (EVC), i.e. on how likely we think it is that exercising conscious control will bring about a desired outcome (cf. ‘self-efficacy’ in Social Cognitive Theory, Bandura (1982); Bandura (1991)). Thus, participants in our workshops often expressed a lack of confidence in their ability to control themselves. This assessment can become self-reinforcing because the confidence in our ability to bring about a desired outcome by exerting conscious control influences how likely we are to try in the first place (Dixon and Christoff (2012); see section 3.2.5). Hence, we might be able to scaffold self-discipline through interventions aimed at making people more confident in their own ability to control their use of digital devices. To design for this, we might consider interventions that at each training step provide a level of support that is ‘just enough’ for the user to succeed while providing a sense of achievement, which could over time increase general confidence in one’s ability to control use (Deci and Ryan 2000).

Third, we might focus on how much reward users expect to gain from exercising self-control (Dixon and Christoff 2012), i.e. on the EVC’s ‘reward’ component. Whereas some existing interventions such as Forest (Seekrtech 2018) provide extrinsic incentives to control use (e.g., a virtual tree that may flourish or perish), a similar route to self-discipline might be by cultivating a intrinsic reward from being in control (Deci and Ryan 2000). One potential approach to this focuses on personal identity, as a changed sense of identity can shift the cognitive evaluation of costs and benefits of the behaviours one has access to, and thus be a powerful means of promoting lasting behaviour change (Caldwell et al. (2018); see Nir Eyal’s recent suggestion to cultivate a personal identity as being ‘indistractable,’ Eyal (2019)). To design for this, we might help users associate particular patterns of use with specific, identifiable personas, and provide just-in-time reminders of how current use aligns or misaligns with the person they aspire to be.

6.5.3 The value of an active workshop approach

In digital mental health research more broadly, ‘solution-focused’ research approaches similar to our work in this chapter have been advocated as a remedy against the large research-to-practice gap in which interventions found to be effective in randomised clinical trials (RCTs) often fail to be useful in real-world implementation efforts (David C. Mohr, Riper, and Schueller 2018). A solution-focused approach prioritises developing a working solution to a practical problem, which can then be adapted to other contexts (D. Mohr 2019). In digital mental health, this approach has in recent years been explored by the ‘IntelliCare’ project, a modular platform for Android that includes 12 apps which deliver psychological interventions for common mental health challenges. Similar to HabitLab (Kovacs 2019), researchers have continuously improved the real-world usability of this platform, while conducting controlled studies of, e.g., effects of coaching assistance (David C. Mohr et al. 2019; David C. Mohr et al. 2017).

In this chapter, our methods were in particular inspired by Cecchinato (2018), whose two-hour workshops for ‘improving control over work-life balance as a result of communication technology’ (conducted with 17 participants) included reflection followed by exploration and commitment to trying out specific interventions. Aside from a slight difference in framing of the workshops, the main differences were (i) the study population (Cecchinato (2018)’s participants were ‘knowledge workers’ with a mean age of 38 years, and included a UX designer & researcher and a communications consultant), and (ii) the interventions included (Cecchinato included e.g. broader social tips for ‘expectation management’; we included only interventions related to digital environments, including the extensions for removing distracting website elements).

Whereas a couple of existing studies have evaluated DSCTs via practical field deployments (I. Kim et al. 2017; Ko et al. 2016; Löchtefeld, Böhmer, and Ganev 2013), the workshops presented in Cecchinato (2018) and this chapter, as well as HabitLab (Kovacs 2019), are the first to include a broader range of research-informed interventions in a single, solution-focused intervention. Given current research gaps around how to tailor digital self-control interventions to personal device ecologies, lifestyles, and personalities, these approaches are likely to prove important for future research.

6.5.4 Limitations & future work

This study has a number of limitations.

First, it was a mainly qualitative case study with a small sample of self-selected students who already struggled with controlling their digital device use. As such, further studies are required to assess how our findings generalise to students or other populations, or to users who struggle at varying degrees. However, we expect many characteristics of our participants, such as lack of work-life separation, heavy reliance on coordination of activities via social media, and frequent motivation to escape arduous work tasks via digital distractions, apply to information workers more broadly, as well as other populations transitioning to remote working.

Second, our results may be biased by demand characteristics (Nichols and Maner 2008). That is, whereas open-ended group discussion was an important feature of the workshops, participants’ reported struggles and goals will have been influenced by what they felt was acceptable to report in the context of their groups and the presence of the facilitator(s).

Third, only half of participants responded to the two-month follow-up (for participants in the fourth workshop, the survey was sent amidst the COVID-19 pandemic). Therefore, the picture of the workshop’s practical usefulness from the follow-up could be biased: for example, it might be that more enthusiastic participants were more likely to fill in the survey.

Fourth, the variation in preferences indicated by participants’ sorting of digital self-control interventions may not be indicative of similar variation in the interventions that are actually effective. Further research is needed to assess how personal expectations around the usefulness of existing solutions relate to actual usefulness, and which factors might predict individual differences.

As will be laid out in section 7.5, we plan to address some of these limitations in future iterations of the Reducing Digital Distraction Workshop: we will explore how to scale the workshops by embedding them in the catalogue of well-being offerings at our partner universities, as well as by trialling specific elements in an online intervention. In a larger-scale deployment, we plan to incorporate measurements of personality and other relevant individual difference variables, and conduct formal efficacy evaluation of the workshops as a mental health intervention.

6.6 Conclusion

To ensure that digital devices have a net positive effect on mental well-being, users must be able to stay in control. To achieve this, we need to understand how to provide interventions against digital self-control struggles that are appropriate to personal circumstances. The study presented in this chapter helps understand how contextual and individual needs influence effective interventions, by providing the first study of how existing design patterns meet the struggles and goals of a population of university students. Through four ‘Reducing Digital Distraction’ workshops, this chapter contributes (i) empirical evidence on the role of existing digital self-control interventions in addressing struggles among university students, (ii) open materials for an intervention format that uses a broad sample of existing interventions to elicit user needs for such interventions, (iii) design implications for tools that align more closely with users’ wishes via focused, within-app interventions, or by supporting the development of self-discipline over time.

This chapter concludes the empirical work of this thesis. In the next chapter, we summarise and discuss the thesis’ overall contributions, as well as some of the wider methodological and theoretical challenges for digital self-control research.